It’s a famous story, but don’t stop me if you’ve heard it because there’s never been a twist like this: When asked about his fear of police, famed suspense and horror film director Alfred Hitchcock often cited an incident from his childhood wherein he was arrested as a lesson about what happens to naughty little boys. It would become something of a joke later in his life; as a child on the cusp of seven years old, it would not have been terribly funny at all. This incident is the jumping off point for Stephen Volk’s short novel LEYTONSTONE, second installment in THE DARK MASTER’S TRILOGY.

We begin with a young Fred missing his afternoon tea, an impatient father taking him straight away to the police station. There, the policeman takes the boy into custody, refuses to state what he’s done wrong, and leads him to a rather uninviting cell.

With a gasp of fright, the small boy backs away into the room of wee. Of wee-stained underpants. Of fear.

“Now then, now then. I thought you was supposed to be a Well Behaved Little Boy.” The voice rasps just as the lock rasped.

Fred goes quiet.

The peep-hole scrapes shut.

He can hear the echoing of the policeman’s squeaky boots, the shiny key ring chinking on the man’s black hip. He back up further, until he sits on the creaky bed with its nasty symphony of rusty springs.

He looks at the long black shadows of bars cast on the floor. The big, grim door facing him. The four filthy walls.

“Father! Father! Father! Father!”

Another door slams, more distant, but loud enough—startling him, and he starts to sob from the bottom of his little heart. (143)

Continued exposure brings still further details both about the room as well as Fred’s character.

Beyond the window a lamp-lighter whistles My Dear Old Dutch. Fred weeps quietly to himself as a glow from outside illuminates the cell with a dull triptych thrown onto the back of the door. He pulls up a moth-eaten blanket over his cold, bare knees. The blanket has a hole in it. It also smells of something vile. Fred sniffs it and his face is punched by the rank niff of stale urine. Piss. He thinks of the word they use in the playground. Piss. (144)

There, he remains for the night, suffering the terrors of abandonment, fearing the unseen but oft heard strangers in cells around him (one who might just be Jack the Ripper), nurturing doubts about himself, and otherwise being terrified by the rude copper in charge who makes regular appearances to let him know he’s essentially rotten. It’s a chilling sequence, and when on the following morning he is released back into the custody of his father, the lad is changed. The remainder of the story will reveal just how changed, as well as playing into several of the blossoming film auteur’s themes and motifs in clever and unsettling fashion. The tale goes some surprising and lightless places as Fred discovers a fascination with the off color jokes his schoolyard pals can pull (e.g., the lads’ most outspoken member/leader invites one of the girls from the neighboring school to put her hand in his pocket for a “treat” that turns out to be living vermin) and a developing friendship with a blonde haired girl, which turns into an obsession that leads young Fred into an unsavory exploration of the thin line between a jest and terror. Little Fred might have emerged from that cell and its implications unscathed in body, but he has not escaped the unseen scars of trauma.

As I mentioned last week in my consideration of Volk’s work on Peter Cushing, WHITSTABLE, I am sensitized to portrayals of artists. It is too easy to zero in on the artists being a rote reporter of the world he sees. In the case of Alfred Hitchcock, it would be no difficult task to focus upon this one incident as the root cause of the director’s repulsion-fascination with tales of suspense, horror, and the ghastly. Too often such focus plays to generally believed but nevertheless nonsense notions that artists are really just lousy journalists in general, and that folks who work in the worlds of fear and terror need to be repulsive or unhinged in some fundamental way to indulge such interests. Because “normal folks” shouldn’t/wouldn’t/couldn’t have “those kinds of thoughts.”

However, Volk once again sidesteps this bias of mine with his work, choosing to instead use this incident as a catalyst for the events of a secret history-type story that follows. What do I mean by secret history? Well, it’s the sort of thing writers such as Tim Powers (author of DECLARE) and F. Paul Wilson (author of BLACK WIND) write to excellence, finding an undocumented spot in an otherwise well-documented history to inject a little of the fictional and perhaps a little of the fantastic.

Volk’s narrative is not content to present the artist Alfred Hitchcock as the product of a single night or a single incident. Fred is a lad who has a collection of macabre items tucked away, things that allude to the course his life will take.

His bedroom is barely bigger than the awful police sell—but not cold, and not dirty, not for dirty people. It’s warm, and tidy. The way he likes it. A place for everything and everything in its place. Puzzles and games on the top shelf, books on the bottom. Picture books to the right, novels to the left. In alphabetical order, by the author’s surname. Just like they should be. Conan Doyle. Stevenson. Swift. And maps almost obscuring the floral wallpaper beneath—the London Underground, together with the Trans-Siberian Railway. He doesn’t suppose he’d ever be lost in Siberia, but if he were, he’d know his way around, at least. Knowing maps means you know your way around everywhere. If you know your maps you’ll never be afraid. (169-170)

In his drawer waits a stack of magazines, including a copy of Life featuring the Statue of Liberty on the cover and shiny pages featuring photographic content and advertisements, all of which titillates his pleasure centers:

Though what kind of pleasure is a mystery. A secret. The kind of secret spies pay money for. And grown-ups kill for. And he devours it. Every word. (170)

As well, there are cinema magazines, a copy of The Illustrated Police News featuring stories on Whitechapel’s infamous horrors, and an issue of Motor Stories pulp fiction magazine. And on the wall? A painting of Jesus:

. . . on the coast of Galilee , hands offered, chin upturned, in beatific mode, the blood-red ‘Sacred Heart’ bursting from his chest with golden rays of light. So well painted, his other says, that “the eyes follow you round the room.” And they do. He knows that because he’s tried going into every corner, but wherever he does, Jesus is watching. (170)

I like this overview of Fred’s interests, brief as it is, because it shows this young man as a collector of ideas from many sources, some consciously and others unconsciously. Sure, bits of the narrative play on some of the famous images and themes from the pictures an older Hitch would make—the spyhole Norman Bates uses to watch Marion Crane in 1960’s PSYCHO (which was admittedly originally called out in the Robert Bloch novel), the “can such a normal person really be Jack the Ripper?” suspicions that showed up in a picture like THE LODGER: A STORY OF THE LONDON FOG (1927), the psychological manipulations of a blonde haired beauty in GASLIGHT (1944). There are more touches, of course. Allusions to SHADOW OF A DOUBT (1943) and FRENZY (1972) and quite a few more in between. However, Volk’s short novel is not content to play solely with suspense and horror influences. He gives us a view into Hitchcock’s love for images of rich foods, by serving up several himself in the story’s domestic scenes.

The piece has enough verisimilitude to add levels of unease I was not expecting. I am not a Hitchcock scholar, more a fan of his works than an aficionado of his life, and there were several times where I had to pause my reading because the material was venturing down too dark pathways, leaving me wondering what Volk was doing to my beloved Hitch (while a gullible part of my mind wondered if the author’s research revealed some unknown-to-me incidents in Hitch’s youth?). Of course, the author was doing nothing to Hitch, and Volk did not unearth real incidents in Hitch’s youth. He instead spins a “What If” yarn about Fred. That detail gives us one avenue for understanding what’s going on under the surface. I’d argue the distinction here—Fred not Hitch—is a deliberate one.

I am typically loath to discuss the climax and conclusion of works in considerations such as this, preferring to keep any spoilers low. However, suffice to say that the book’s ending recasts the material as a whole. I shall not reveal details about the plot’s conclusion—read it and marvel—however, I will call upon the coda to give another perspective on the details. Readers wishing to have an “unspoiled” experience for themselves are encouraged to skip the next two paragraphs.

After reaching the end of the emotional roller coaster involving Fred’s night of terror and his subsequent grappling with his own nature of good or evil (well, in his own youthful perspective this might better be described as his nature as a well-behaved boy or bad one), the short novel offers a view of the director in one of his final appearances, an unwell adult receiving the accolades and appreciations of his chosen industry and its professional members. At first, this sequence might not seem to fit with the harrowing tale we have just read about the ripple effects of a traumatic incident. However, it’s here for a reason and is, in fact, the clincher to tell us all about the events we have just witnessed.

An artist is not a mere reporter of what s/he has seen and done. They are instead a synthesizer of inputs, be they from stories they have read, subject matter that somehow captured their imagination, of even the events they have participated in through their lives. Creators all cherry pick inputs and instances, building upon them to create their stories. There are enough factual deviations from Hitch’s life in young Fred’s story (as well as the insistence on calling the character Fred instead of using the director’s preference for “Hitch”) and there are character differences that might be rationalized away as the development steps kids pass through while discovering they are not the centers of the universe but bit players in epic productions. However, that finale gives the piece another reading: The entire narrative might well be the kind of story a director like Hitch would have conceived making, something rattling around in his head at the tail end of his life, a tale that draws upon his own past but viewed through a darker lens, a screen story that would play to his always droll, often macabre, and occasionally perverse sense of humor as well as his predilection for exploring the evils human beings are capable of performing to one another, but which he would never have the chance to put into production. Viewed in that light, Fred’s journey takes on a second intriguing layer. Fred might therefore be the spiritual film-negative flip-side to the character Alfred Hitchcock played as the droll and macabre narrator to his television series or trailers for flicks like PSYCHO and THE BIRDS. The story becomes less an exploration of the traumatized bad boy lurking in the hidden past of a purveyor of scary, thrilling delights than it is a canny view into the artist’s process of taking life events and reshaping them into something new: an engaging, jolting, and resonant story.

While the first part of THE DARK MASTERS TRILOGY brought tears to my eyes with its conclusion, LEYTONSTONE made me grin at the author’s audacity and cleverness. It’s a chilling exercise, easy company with some of the late Jack Ketchum’s explorations of the darkness that blossoms inside the human heart. However, it is neither a graphic nor gratuitous piece. It is a near-perfect Alfred Hitchcock movie for the mind’s eye, a page-turner that offers sinister delicacies, flirts with the perverse, some uncomfortable revelations about men and women, and reaps maximum pathos and suspense from its blue collar location and characters.

#

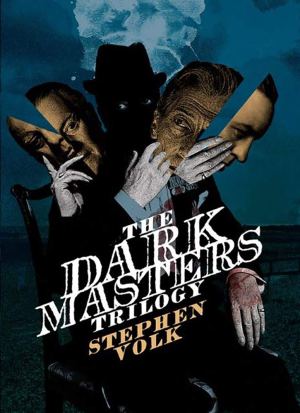

This week’s considered book is Stephen Volk’s LEYTONSTONE, which was first available as a standalone paperback through Spectral Press. That edition is still available these days through third parties. However, the lovely PS Publishing hardcover edition collecting all three parts of THE DARK MASTER’S TRILOGY is available and worth every cent.

Next week, I will take a look at the third work in the trilogy, NETHERWOOD, which pairs up black magic novelist Dennis Wheatley (of THE DEVIL RIDES OUT and TO THE DEVIL A DAUGHTER fame) with The Great Beast 666 Aleister Crowley . . . That short novel seems to be only available in the PS Publishing hardback edition.

Have you bought a copy yet?

WORKS CITED

Volk, Stephen. THE DARK MASTERS TRILOGY. PS Publishing: Hornsea, England. 2018.

“What Terrifies the Master of Suspense: Stephen Volk’s Leytonstone” is copyright © 2019 by Daniel R. Robichaud. Excerpts are taken from the above mentioned edition of Stephen Volk’s work. Cover image taken from the PS Publishing edition of The Dark Masters Trilogy.

2 thoughts on “What Terrifies The Master of Suspense?: Considering Stephen Volk’s Leytonstone”