Meredith Stone (Patricia Pearcy) journeys to a home to serve as a nurse of the elderly Ivar Langrock (Joseph Cotten). When she arrives, she encounters the well-meaning (but prone to drinking) butler Phillip (Leon Charles), the chatty cook Duffy (Alice Nunn), and finally meets the elderly gent she will be serving. He’s a grouchy but likeable paraplegic, who is candid about his expectations. He has high hopes about connecting with his grandson, a young man who he has not yet met but nevertheless looks forward to having as a ward (following the accidental deaths of the boy’s parents).

As it turns out, Gabriel Langrock (John Dukakis) has been raised on a commune in rural Arizona, lacks some of the refinements, social skills, and expectations of life in suburban California. When presented with a skateboard, which all the teenagers are eager to try out, Gabriel would prefer a .22 rifle to hunt rabbits … no, squirrels. He has an affinity for trapping and killing animals as well as no small amount of animal magnetism for Meredith.

Although the Langrock family lawyer Jeffrey Fraser (David Hayward) is interested in her, and she is intrigued by him, she is much more drawn to Gabriel’s raw sexuality and confidence. However, when some mysterious (and increasingly bloody) circumstances start taking place around the manor and its grounds, Gabriel is the first suspect. Is he suffering some kind of homicidal delusions? Or is someone closer to Ivar’s confidence responsible? The Langrock house has some secrets within its walls, including a locked room that might not be as empty as some of the staff proclaim it to be. Already pulled between her job and sexual fascinations, Meredith soon finds herself thrown into the role of Nancy Drew investigator trying to piece together the family’s sinister secrets and protect herself. Co-writer Alan Beattie helms a slice of gothic mystery with the unsettling The House Where Death Lives (1981).

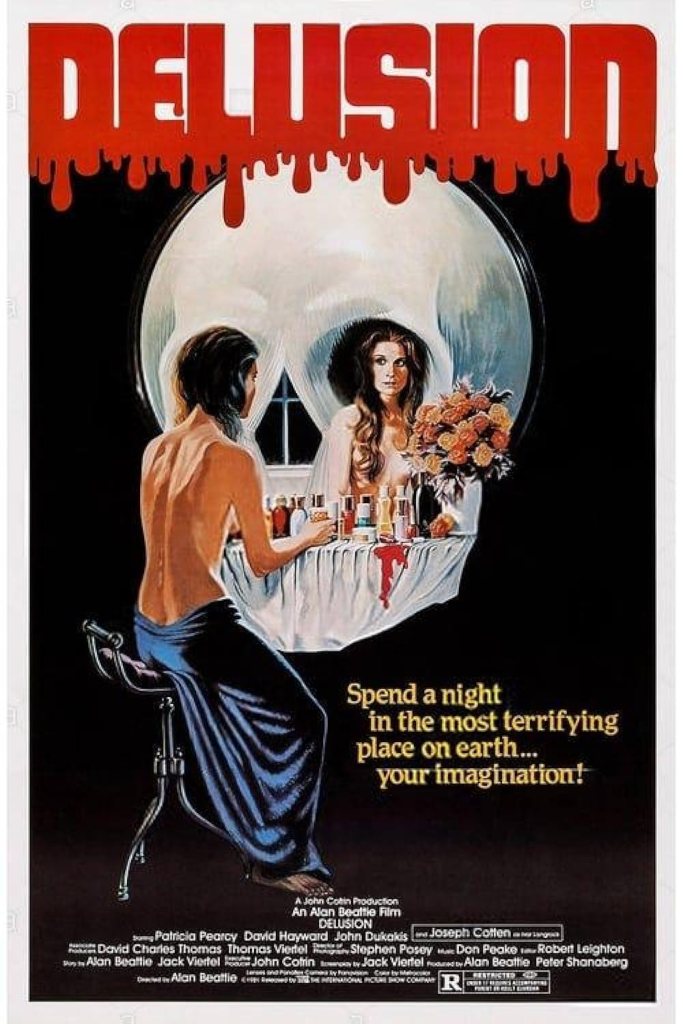

This is one of those flicks with more than one name. Shooting took place under a placeholder name and then initially released as Delusion (and that’s the credit is has on IMDB.com). For its subsequent re-releases (there were at least two in theaters and the eventual appearance on VHS), it has born the name The House Where Death Lives. Neither of these is particularly good at capturing the mood and spirit of the film, though the last one seems the most likely. The flick is classic gothic territory, while both titles suggest something a tad closer to psychological suspense terrain. Either way you look at it, the flick seems to have been composed in a direct opposition to the box office reigning slasher flicks of the time. There’s something classy and classic about this one, a woman journeying to a big old house and serving a family that seem off, who discovers supposedly dead people hidden away in locked rooms and dodging strange killers who lash out from the darkness on some kind of vendetta. While Delusion seems to draw references to Psycho, the story is less Robert Blochian than it is akin to giallo films such as Mario Bava’s The Girl Who Knew Too Much (1969) or gothics like Mino Guerrini’s The Third Eye (1966). It’s all about a vulnerable, modern-day heroine who finds herself in a situation where she cannot help but butt heads with a killer suffering from fugues and delusions. It aims much older for its target audience, and it suffers from a quaintness and restraint during years of excess.

The picture feels akin to a made-for-television production such as Are You in the House Alone? (1978) Some of this is due to the script from Jack Viertel (based on a story by both Viertel and the director), which offers up the kinds of frustrations and family drama stuff that occupied many of America’s screens back in the tail end of the 1970s. There are some love scenes and a couple of topless shots that would prevent this sucker from showing on television without mild editing. However, the swearing, gore, and sex are minimized in favor of atmospheric touches and allusions to such fare.

Cinematographer Stephen L. Posey employs some good lighting for the daytime shots, lending the interior and exterior locations alternately comforting or sinister qualities. The nighttime scenes employ very deep shadows. He would serve as cinematographer and camera operator for a host of pictures in this era, including such exploitation fare as The Slumber Party Massacre (1982), Savage Streets (1984), Friday the 13th: A New Beginning (1985), and more. His career shifts seamlessly between television and feature projects, do it’s unsurprising to see his name attached to CBS Schoolbreak Special episode “The Drug Knot” (1986) and twenty-nine episodes of the Vietnam War drama, Tour of Duty (1987-1989). He has a way of shooting that captures the elements necessary to tell the drama, a way of lighting that serves the images nicely, and an expedient shooting style. Few camera tricks clutter the piece, instead we are treat to a much more grounded capture the shot and move on methodology.

There is a lingering sense of wrongness to many of the characters and their relationships in this picture. Meredith is not a normal character by any stretch of the imagination—from the first shot, something seems off about her. Likewise, Gabriel is an abnormal character as well. This is thanks to the intriguing acting choices both Pearcy and Dukakis bring to their performances. The characters don’t really have modern day analogues; they are off-putting but normal for the era and unsettling for mainstream contemporary audiences to stay with for too long.

Much more enjoyable is Cotten’s penultimate feature film appearance—the man knew how to use every tool in the actor’s kit to make his performance grounded, accessible, mysterious, and inviting. And the best of the performances aside from Cotten is that of James Purcell, who makes a brief appearance as a detective looking into deaths on the Langrock estate’s grounds. He’s got a quirky delivery for routine lines that reveals the heart of the character. It’s a small part that ought to fall into one of those “There are no small parts” sort of exposes since it’s a classy, clever showcase for talent.

The Vinegar Syndrome Blu-ray release of the film includes a lovely transfer from the original 35mm camera negative. It is accompanied by a commentary track from The Hysteria Continues podcasters, which should not be listened to while seeing the film for the first time since it’s happy to spoil film secrets in order to provide context for some of the filmmakers’ choices . There are interviews with the two romantic male lead actors, David Hayworth and John Dukakis as well as a lengthy conversation with author Stephen Thrower about the making of the picture and its place in horror history.

The House Where Death Lives is a slow burn gothic mystery, with elements drawn from early giallo pictures as well as a sinister sort of sexuality that appeals to the gothic romances popular in the late 1970s. One gets a sense that it serves as a kind of stepping stone for the erotic thrillers that would come along later on and the Lifetime network’s particular brand of these sorts of things. It won’t necessarily thrill viewers looking for a solid slasher effort that finds a murderer killing often and gorily because that is not what it intends to provide. Instead, it offers some chills and a few thrills as a mysterious presence strikes from the dark, loosing blood for reasons that are initially unknown and come to light only in the final reel. This is gruesome, perverse whodunit territory, and fans of such fare will find some lovely moments, intriguing performances, and entertainment.

#

The House Where Death Lives/Delusion is available in a Blu-ray edition.

Writing for “Homicidal Delusions: The House Where Death Lives (1981)” is copyright © 2024 by Daniel R. Robichaud.

Disclosure: Considering Stories is a member of the Amazon Associates. Under that program, purchases made using the product links in any of our articles can qualify the Considering Stories site for a payment. This takes the form of a percentage of the purchase price, and it is made at no additional cost to the customer.